Indian Pottery: Traditional Crafts, Techniques, and Living Art Forms

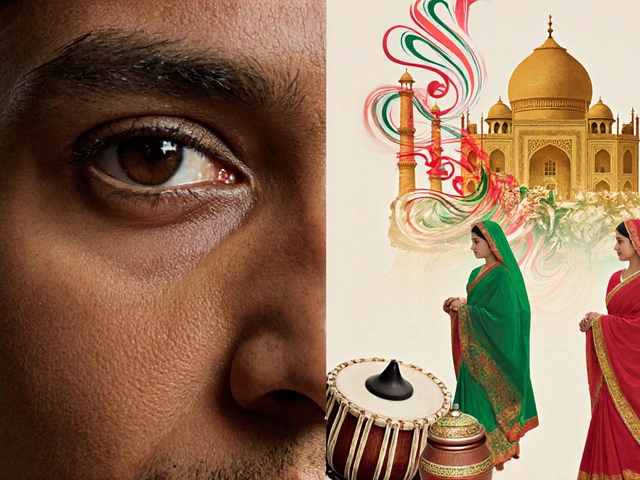

When you think of Indian pottery, hand-shaped clay vessels and decorative objects made across India for thousands of years. Also known as terracotta art, it's more than just containers—it's a silent record of village life, rituals, and regional identity. Unlike mass-produced ceramics, Indian pottery is still made mostly by hand, using techniques passed down through generations. In places like Khurja, Kutch, and Puducherry, potters don’t just shape clay—they tell stories with every coil, groove, and painted symbol.

Indian pottery isn’t one thing. It’s a family of styles, each tied to its land. In terracotta art, unglazed, low-fired clay objects, often used in religious rituals and home decoration, you’ll find figures of deities in West Bengal and animals in Rajasthan. In folk pottery India, handmade ceramics with bold patterns, often used in daily life and festivals, the colors aren’t just pretty—they carry meaning. Red clay from the Ganges plain means fertility. Black clay from Tamil Nadu is linked to ancestral worship. And the intricate white designs on Bengal’s pottery? They’re prayers made visible.

What makes Indian pottery different from other ceramic traditions? It’s alive. You won’t find it only in museums. Walk into a village market in Odisha, and you’ll see women carrying water in hand-thrown surahis. Visit a temple in Gujarat, and you’ll notice the clay lamps lit during Diwali—each one molded by a local artisan. These aren’t souvenirs. They’re tools, offerings, and heirlooms. Even today, entire families live by the wheel, using the same mud, tools, and firing methods their great-grandparents did.

There’s no single book on how to make Indian pottery. You learn by watching. The potter doesn’t measure. They feel the clay. They know when it’s ready by the sound it makes when tapped. The kilns are open fires, not electric ovens. And the glazes? Often made from crushed stones, plant ash, or even cow dung. It’s not industrial. It’s intimate. It’s tied to the soil, the seasons, and the sacred.

And yet, this art is under pressure. Younger generations are moving to cities. Plastic containers are cheaper. But in places like Channapatna and Sankheda, people are fighting back—reviving old designs, teaching kids to spin the wheel, and selling directly to buyers who care about where things come from. You’ll find these stories in the articles below: how a single clay pot in Bihar holds a century of memory, why a village in Andhra Pradesh still paints its vessels with natural dyes, and how a forgotten technique in Rajasthan is being brought back by a woman who refused to let it die.