Key Takeaways

- Indian classical music splits into two major traditions: Hindustani (North) and Carnatic (South).

- Both rely on raga (melodic framework) and tala (rhythmic cycle) but treat them differently.

- Hindustani music grew from Mughal court culture, while Carnatic music stayed rooted in temple rituals.

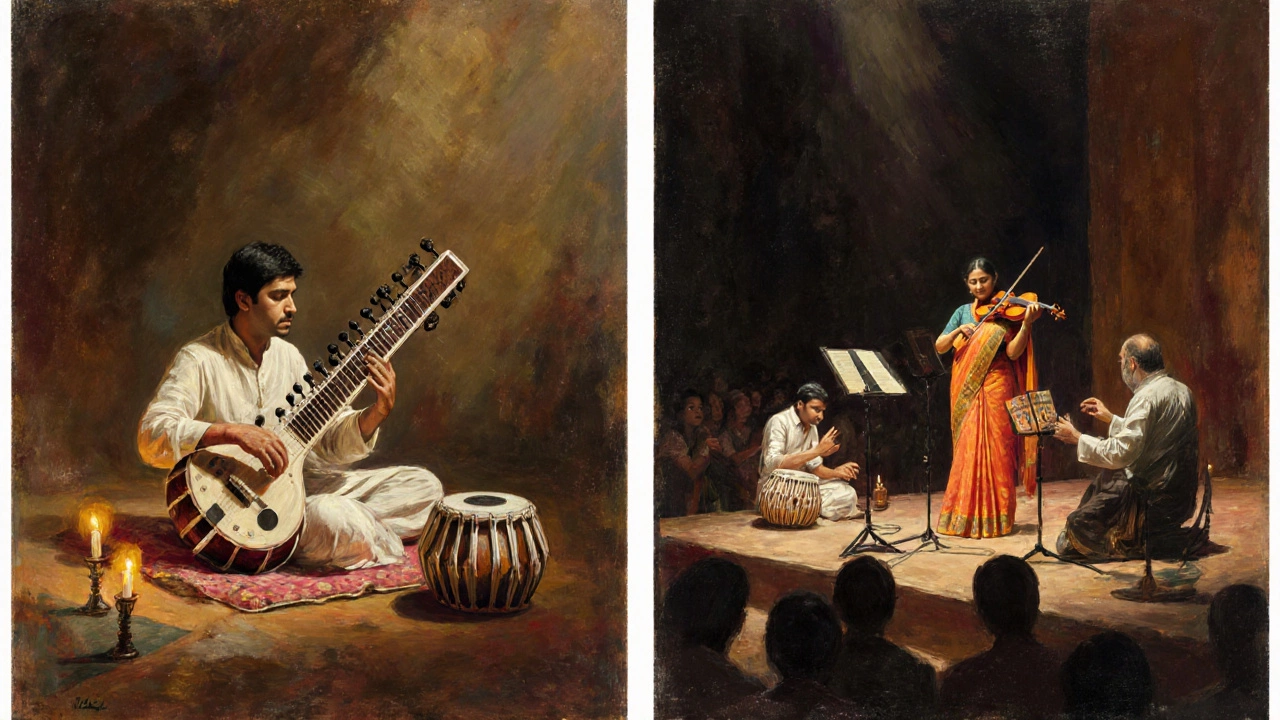

- Typical instruments differ: sitar, sarod, and tabla dominate the North; veena, mridangam, and violin dominate the South.

- Learning paths, repertoire, and performance etiquette reflect each tradition’s history and audience.

What is Indian Classical Music?

When people say Indian classical music, they’re really talking about two distinct streams that have evolved side by side for centuries. Both streams share a core philosophy: music is a spiritual journey, a way to evoke emotion (rasa) and connect with the divine. The two streams are:

Hindustani music is a North Indian tradition that blossomed under the patronage of Mughal courts, Persian musicians, and later, British colonial institutions. It emphasizes improvisation, slow development of a raga, and a flexible approach to rhythm.

Carnatic music is a South Indian tradition that grew out of temple worship and royal courts in the Deccan. It focuses on compositional rigor, complex rhythmic patterns, and a systematic teaching method.

Understanding these two pillars helps you answer the original question: the counterpart to Hindustani is Carnatic.

Hindustani Music: Roots, Structure, and Sound

The word “Hindustani” comes from “Hindustan,” the historic name for the northern Indian plains. Its major milestones include:

- Historical Influences: The Mughal Empire (1526‑1857) introduced Persian melodic ideas (ghazal, dastgah) and instruments like the sitar and tabla. The British era brought formal music schools, most notably the Bhatkhande Music College, standardising theory.

- Key Concepts: A performance usually starts with an alap-a slow, rhythm‑free exploration of the raga. It then moves into a jor and jhala (if on plucked strings), before the rhythmic gat with tabla accompaniment.

- Typical Instruments: Sitar, sarod, shehnai, bansuri (flute), and the tabla pair (right-hand dayan, left-hand bayan).

- Prominent Figures: Ravi Shankar, a sitar virtuoso who introduced Hindustani sound to Western audiences, and Ustad Zakir Hussain, a tabla maestro known for cross‑cultural collaborations.

Hindustani improvisation hinges on the artist’s ability to unfold a raga gradually, often lasting 30‑45 minutes per piece. Rhythm is handled through cycles called tala, ranging from the simple 8‑beat teen taal to the sprawling 108‑beat sashat tala.

Carnatic Music: Roots, Structure, and Sound

Carnatic music’s heart beats in the southern states of Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh. Its development can be traced through three phases:

- Temple Foundations: Ancient treatises like the Natya Shastra and the devotional poetry of the Bhakti movement set the stage. Music was performed as part of worship, linking melody directly to spiritual offering.

- Compositional Emphasis: The genius of the Trinity-Tyagaraja, Muthuswami Dikshitar, and Syama Sastri-produced thousands of kritis (fixed compositions) that remain the backbone of concerts today.

- Modern Institutionalisation: The early 20th‑century Carnatic Music Schools, like those started by the Mysore brothers, formalised teaching and created graded examination systems.

Key characteristics:

- Raga Treatment: A raga is presented through a fixed sequence-alapana (improvised), kriti (composition), niraval (melodic variation), and kalpana swaras (improvised swara passages).

- Rhythmic Complexity: tala cycles range from the ubiquitous 8‑beat adi tala to the intricate 9‑beat khanda chapu. Percussionists (mridangam, ghatam, kanjira) often engage in elaborate thanavams (rhythmic improvisations).

- Instruments: Veena (plucked lute), violin (adapted for Indian tuning), mridangam (double‑headed drum), and the bamboo flute venu.

- Notable Exponents: M.S. Subbulakshmi, whose voice popularised Carnatic music globally, and L. Subramaniam, a violin virtuoso known for both tradition and fusion.

Side‑by‑Side Comparison

| Aspect | Hindustani | Carnatic |

|---|---|---|

| Geographic Origin | North India (Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Delhi) | South India (Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Kerala) |

| Historical Patronage | Mughal courts, Persian influence | Temple rituals, Deccan royalty |

| Primary Instruments | Sitar, sarod, tabla, bansuri | Veena, violin, mridangam, ghatam |

| Performance Structure | Alap → Jor/Jhala → Gat (with tabla) | Alapana → Kriti → Niraval → Kalpana Swaras |

| Raga Approach | Gradual, mood‑focused exploration | Composition‑centered, with preset phrases |

| Tala System | Flexible cycles (e.g., teentaal 16 beats) | Fixed cycles, heavy emphasis on math (e.g., adi tala 8 beats) |

| Famous Composers | Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Amir Khan | Tyagaraja, Muthuswami Dikshitar, Syama Sastri |

How to Start Learning Either Tradition

Choosing a path depends on where you live, what instruments you’re drawn to, and the kind of musical experience you crave.

For Hindustani Aspirants

- Find a gharana (school) that matches your style-like the Maihar, Kirana, or Patiala lineages.

- Begin with basic raga and tala exercises on the tanpura and tabla.

- Online platforms such as Saregama Academy and the ICCR’s outreach programs offer free introductory courses.

- Attend live concerts in Delhi’s Dilli Haat or Mumbai’s National Centre for the Performing Arts to absorb the ambience.

For Carnatic Fans

- Enroll in a gurukula‑style school or a local institute that follows the *gurukula* teaching model.

- Start with simple varnams (introductory pieces) on the violin or veena.

- Practice the 8‑beat adi tala using a mridangam teacher or digital tala apps.

- Watch the annual December Music Festival in Chennai-an unmatched showcase of tradition and improvisation.

Both traditions value *guru‑shishya* (teacher‑student) relationships, so personal mentorship often outweighs any self‑study method.

Current Scene and Fusion Trends

Modern musicians blend Hindustani and Carnatic vocabularies with jazz, rock, and electronic beats. Artists like Shakti (John McLaughlin & Zakir Hussain) and the late Rahul Sharma fuse tabla rhythms with Western guitar. In the South, the *fusion band* *Agam* mixes Carnatic melody with progressive rock, attracting younger crowds.

Despite these experiments, the core frameworks-raga, tala, and the respective performance etiquette-remain intact, ensuring authenticity while allowing innovation.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main difference between Hindustani and Carnatic music?

Hindustani music leans on improvisation and a slower, mood‑building raga development, while Carnatic music is built around complex, pre‑composed kritis and mathematically intricate tala patterns.

Which instruments are unique to each tradition?

The sitar, sarod, and tabla are hallmarks of Hindustani music. In Carnatic music, the veena, mridangam, and violin (adapted to Indian tuning) dominate.

Can I learn both Hindustani and Carnatic styles simultaneously?

It’s possible but challenging because each system has its own grammar, ornamentation, and rhythmic logic. Most students start with one tradition, then explore the other after gaining a solid foundation.

How do I identify a raga I’m hearing?

Listen for the jazzy notes (vadi and samvadi) that receive emphasis, the ascent (aaroh) and descent (avroh) patterns, and any characteristic phrases (pakad). Apps like “Raga Explorer” can help you match what you hear to a specific raga.

Where can I watch live Indian classical concerts online?

Platforms such as Sangeet Natak Akademi’s streaming service, the ICCR YouTube channel, and cultural festivals like the Dover Lane Music Conference often broadcast full performances for free.